Our Magazine

Chronograph Dials Explained: What All Those Little Dials Do

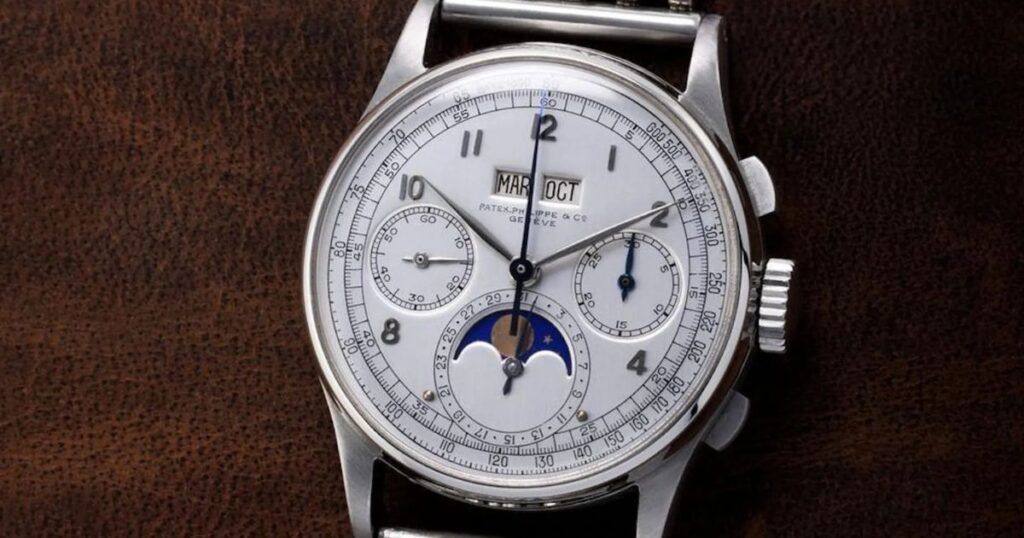

If you’ve ever admired a chronograph watch and wondered about the smaller dials on its face, you’re not alone. These subdials, or counters, transform a simple timepiece into a sophisticated instrument of precision and functionality. In this deep dive, we’ll unravel the mystery behind chronograph dials, exploring their roles, historical significance, and why they remain a cornerstone of fine watchmaking.

The Basics: What Is a Chronograph?

Before we dissect the dials, let’s clarify the term. A “chronograph” derives from the Greek words chronos (time) and grapho (to write). Simply put, it’s a watch with a built-in stopwatch function, independent of the regular timekeeping. These watches typically feature two or more pushers on the case to start, stop, and reset the timing mechanism. The beauty lies in the subdials, which display the recorded elapsed time.

Deconstructing the Subdials

A standard chronograph usually has two or three small dials on the main watch face. The configuration can vary, but the most common is the tri-compax layout (three subdials). Here’s a breakdown of their typical functions:

1. The Seconds Dial (Continuous Seconds)

Often positioned at 9 o’clock, this dial might seem redundant at first glance. After all, doesn’t the main seconds hand tell the time? In many chronographs, the large central seconds hand is actually dedicated to the stopwatch function. The small subdial at 9 o’clock is therefore responsible for continuously running seconds for regular timekeeping. This separation of functions is a hallmark of traditional chronograph design, ensuring clarity and precision.

2. The Chronograph Minutes Counter

Located frequently at 12 o’clock or 3 o’clock, this subdial tracks elapsed minutes once the chronograph is activated. The central chronograph seconds hand can only measure up to 60 seconds. After one full rotation, the minutes counter will advance by one increment, typically allowing tracking of 30 or 60 minutes. In more complex chronographs, this can extend to 12 hours.

3. The Chronograph Hours Counter

In watches with a 12-hour totalizer, you’ll find a third subdial, often at 6 o’clock. This records the elapsed hours during a timing session. For example, timing a long event like a marathon or a work shift becomes possible. When the chronograph minutes hand completes its cycle (say, after 60 minutes), this hours counter advances by one.

4. The Day/Date and Other Complications

Some chronographs incorporate a day or date window, or even use a subdial for the date. Others might feature a tachymeter scale on the bezel or outer rim. This scale allows the calculation of speed based on time traveled over a fixed distance—a classic tool for racers and engineers.

Beyond the Standard: Advanced Chronograph Date

High-end watchmaking introduces fascinating variations:

- The Bi-Compax (Two Subdials): A cleaner, often vintage-inspired layout combining functions. One subdial might handle both running seconds and a 30-minute counter, requiring more intricate mechanics.

- The Flyback Chronograph: Allows instantaneous reset and restart with a single push, crucial for pilots. The dials look standard but house a more complex mechanism.

- The Rattrapante (Split-Seconds Chronograph): Features an additional central seconds hand. This complication can time multiple events that start simultaneously but end at different times. It often requires additional subdials or markers to manage this function and is a pinnacle of watchmaking artistry.

- The Decimal Chronograph: Tracks time in more industry-specific increments, like 1/100th of a minute, displayed on a unique subdial scale.

A Note on Movement and Layout

The arrangement of these subdials is not arbitrary; it’s dictated by the movement inside. The most common configuration for modern automatic chronographs is subdials at 3, 6, and 9 o’clock. This stems from the modular architecture of iconic movements like the Valjoux 7750. In contrast, vintage or manually-wound chronographs, or those using a column-wheel mechanism, might feature a “reverse panda” or “panda” layout with subdials at 12, 6, and 9 o’clock—a design beloved by collectors for its symmetry and historical pedigree.

Why It Matters: The Soul of the Instrument

Understanding these dials is about more than just functionality; it’s about appreciating a micro-engineering marvel. A chronograph is one of the most popular complications because it represents a perfect marriage of technical ingenuity and practical utility. Each subdial is driven by a network of additional gears, levers, and clutches seamlessly integrated into the base movement. When you operate the pushers and watch the hands sweep and snap back, you’re engaging with over a century of horological innovation.

How to Use Your Chronograph

- Start: Press the pusher usually located at 2 o’clock. The central seconds hand and relevant subdials will begin to track elapsed time.

- Stop: Press the same pusher again to halt timing.

- Reset: Press the pusher at 4 o’clock to return all chronograph hands to zero. This should only be done after the stopwatch is halted.

- Reading: Combine the data. For instance, if the central hand points to 25 seconds, the minutes counter shows 10, and the hours counter shows 1, the total elapsed time is 1 hour, 10 minutes, and 25 seconds.

In Conclusion

The little dials on a chronograph are the windows into its complex soul. They transform the watch from a passive object telling time into an interactive device that measures it. From timing a perfectly boiled egg to calculating lap speeds or simply admiring the symphony of moving parts, the chronograph offers a tangible connection to precision mechanics. The next time you glance at one, you’ll see not just three small dials, but the legacy of human ingenuity on the wrist.

So, whether you’re drawn to the classic tri-compax, the sleek bi-compax, or the sophisticated split-seconds, remember: each subdial tells a story of purpose, history, and unparalleled craftsmanship.